This week we will be looking back to a time when a Charmouth gentleman tried to help royalty escape the country.

The man in question was William Ellesdon, whose family hailed from Lyme Regis, who made a name for himself due to his attempts to get future King Charles II to safety from the parliamentarians.

Information and pictures for this piece have been provided by Neil Mattingly.

From 1642 until 1651, the English Civil War not only divided the country, but left families divided, and no more so than the Ellesdons.

The family had been staunch royalists in a town that supported the parliamentary forces.

Before the war began in 1641, parliament decreed that all males over 18 should take a 'Protestation (declaration of loyalty) Oath'.

All names were listed and anyone who refused to take it was recorded, and in Charmouth, 75 gentleman were to sign it out of a population of 250.

In 1644, Dorset was pulled into the action of the war, as Lyme Regis was besieged by Prince Maurice and the royalist army, who heavily outnumbered the parliamentary forces in the town.

However, the town held on for two months, getting supplies from the sea until the royalists left.

The head member of the Ellesdon family in 1649 was Anthony, who had earlier stood down as mayor, and it was he who was to purchase Newlands Manor on the edge of Charmouth in 1649.

The same year his son William bought Charmouth Manor, whilst his brother, John, remained in Lyme Regis and was known to support Oliver Cromwell, which created divided loyalties within the family.

William rose to the rank of captain in the royalist army and fought in a number of battles for them.

The royalists were finally defeated at the battle of Worcester on September, 3 1651 and the young Charles, who was yet to be king of England, attempted to flee the country to France.

One famous occasion saw the king-to-be hide in an Oak Tree at Boscabel, with his enemy just below him.

By September, 17 1651, Charles was known to be hiding at Trent, on the outskirts of Sherborne, in a manor owned by the Wyndham family.

The family told Charles that Captain William Ellesdon of Charmouth had already assisted Lord Berkley to the continent, and a plan was made for Charles to stay in a house owned by Ellesdon's father at Monkton Wylde, which is still today called Elsdons.

A side of the farm house still has the plaque commemorating the visit.

William had arranged that Stephen Limbry, who was a sailor and a tenant of his, would take the king-to-be to a ship moored off the coast from Charmouth Beach.

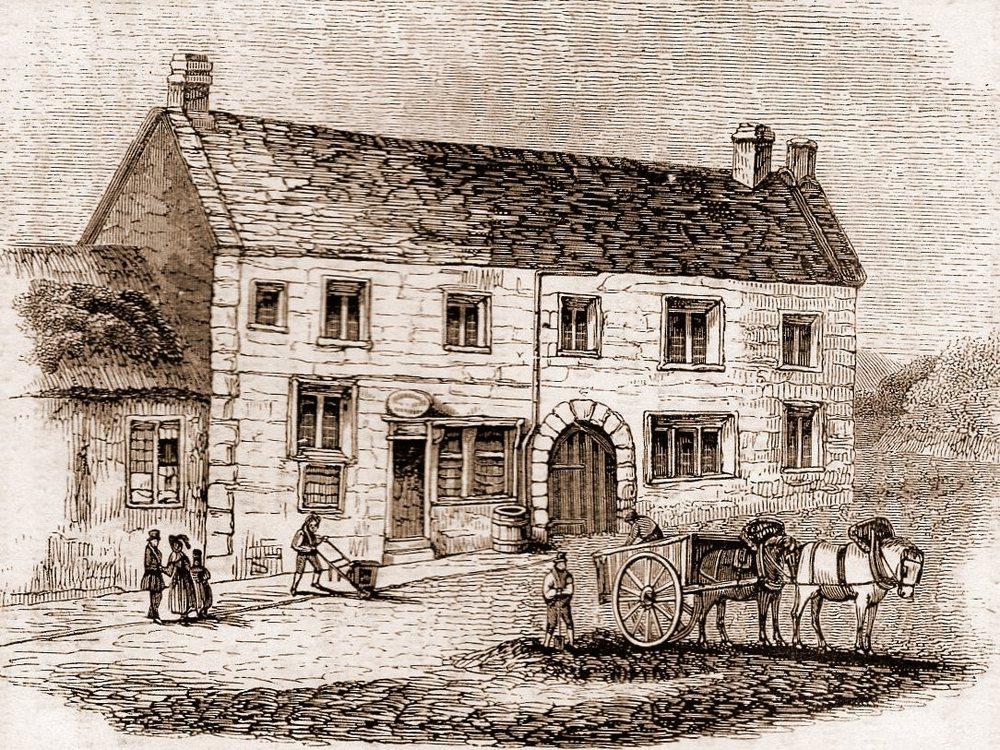

Charles was to visit Charmouth and spend the night in what was then "The Queens Armes", but today is "The Abbots House".

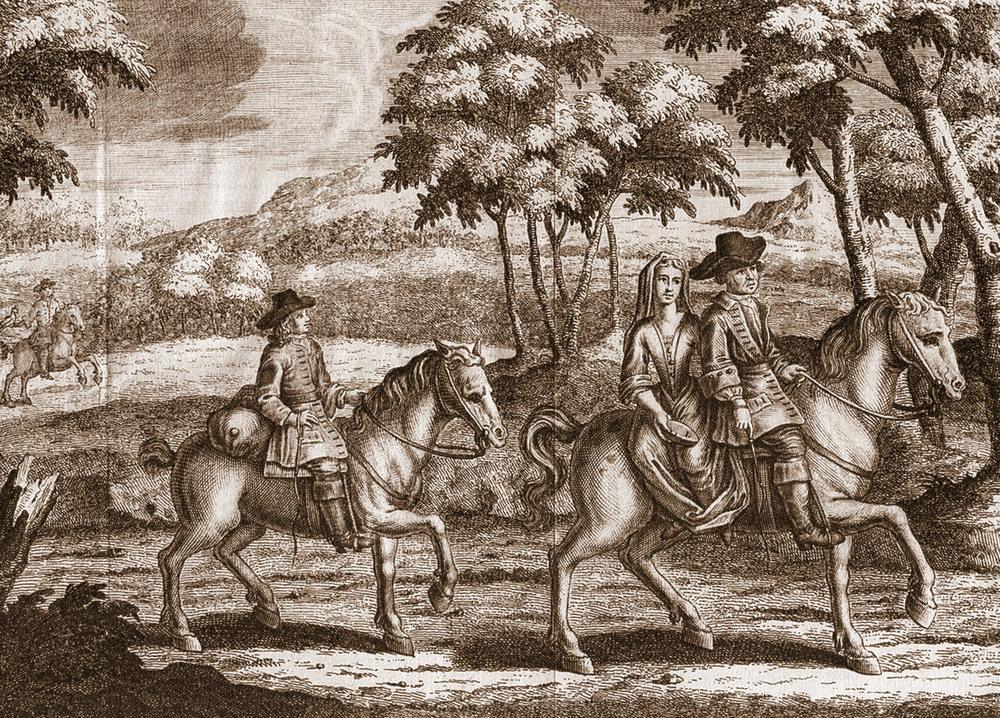

He would do so in disguise with the niece of Lady Wyndham, Juliana Coningsby, pretending to be a runaway couple.

Stephen Limbry had returned home before the meeting to discuss the future king's passage, but found himself locked in by his wife and two daughters.

Limbry's wife, who had her suspicions after her husbands late-night adventures, had visited the market in Lyme Regis earlier during the day to see the posters and a reward of £1000 for information leading to the capture of the future king.

It was likely that anyone helping him would have been executed for treason if caught.

Had it not been for Limbry's wife, Ellesdon would have been successful in helping another royalist escape to France.

By the time Limbry had escaped, Charles had decided he could wait no longer and took the road to Bridport, where he was nearly captured.

After a week away, Charles returned back to the safety of Trent, and finally left these shores near Shoreham on October, 15.

At the end of the Civil War, after Charles' coronation to the throne of England, Ellesdon was gifted with a medal for his efforts, as well as a pension of £300 per annum for himself and his two successive heirs.

The pension was for both him and his immediate family and would be derived from taxes received from the port of Lyme Regis.

Unfortunately, the money was often not received, despite pleas from his family for the outstanding payments.

Ellesdon died in 1684, the year before the Monmouth Rebellion, but his pension was to continue to be received by his wife, with son Anthony taking over his role.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here